Congress allocated a historic amount of federal funds to tribes through the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act and the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act. For some Indigenous communities, those federal funds were beneficial. For others, the pandemic highlighted deeper systemic complexities federal funding cannot fully address.

Indigenous nations across the country have experienced chronic federal underfunding, which has led to disproportionate impacts tied to COVID-19 through housing, employment, public safety, food security, health care and economic outcomes.

In March 2020, the CARES Act established the Coronavirus Relief Fund, which allocated $8 billion to tribal governments and Alaska Native Corporations to address “necessary expenditures” incurred due to COVID-19.

One year later, American Rescue Plan Act funds allocated $31 billion for infrastructure needs and other federal programs for Indigenous communities.

Additionally, $1 billion is being divided and dispersed to each eligible tribal government, and $900 million was allocated for several purposes, including tribal housing improvements.

Congress also allocated funds to various Indigenous entities through smaller COVID-19 relief bills: $2.6 billion from the Consolidated Appropriations Act, no less than $750 million plus a share of no less than $11 million from the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, and $74 million from the Families First Coronavirus Response Act.

“What we learned was, even though money was allocated, we were still running into a lot of issues,” said Eugenia Charles-Newton, a council delegate for the Navajo Nation. “There were so many rules from the U.S. Department of Treasury regarding the CARES … that made it really difficult to try to spend that money where it was needed.”

The Blackfeet Nation received $38,692,273 in CARES funding, according to Richard K. Delmar, acting inspector general for the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

But Marietta Green, a Blackfeet elder who lives on the Blackfeet Reservation in Browning, Montana, said she has been waiting for the tribal housing department to address her problems for years.

Green lives in a four-bedroom house where she raises three grandchildren. She said her home has high levels of mold, her plumbing is unpredictable and her lights get shut off around 11 a.m. when her electric bill isn’t paid on time.

The tribe distributed $500 checks to enrolled members 18 and older from CARES Act funds. Green said she used her check to buy food and take care of her grandchildren.

A cross hangs on the door of Marietta Green’s home on the Blackfeet reservation in Browning, Montana. (Beth Wallis/News21)

Green said she covers the windows in the house’s back rooms to keep out the cold Montana winters where the temperatures can dip below zero. Many windows are broken or too drafty to keep warm, she said.

“The housing authority, they’re supposed to be the authority,” Green said. “They’re supposed to be there for us, they’re supposed to be helping us maintain these places and giving us equipment so we could maintain these places … But they won’t help me.”

Green said when she moved in about 25 years ago, the housing department helped with rental assistance, but that stopped. Green applied for rent and water assistance through the tribe and has been told by the housing department her one-time assistance check is on the way.

Tribal members like Green said they are troubled by the lack of transparency from their government on how CARES Act funding was spent. On June 21, 2021, tribal members Green, Laura Smith and Leona Gopher protested for better transparency in front of the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council office in Browning, Montana.

Marietta Green stands on her family’s land on the Blackfeet reservation in Browning, Montana. Green said she hopes to someday build a house and move out to the remote area. (Beth Wallis/News21)

Business Council members, including current tribal chairman Timothy Davis and Blackfeet Public Information Officer James McNeely did not return multiple requests for comment about how CARES Act funds were spent.

“I’m tired of what they do to us — it’s disgusting,” Smith said. “And all of our heads count for all the money they get. That’s why I’m down here protesting, because I’m tired of it.”

Smith lives in a two-bedroom house and raises three daughters and three grandchildren. She said she receives disability payments, and has lived in her house for roughly 38 years.

With the onset of the pandemic, however, times have gotten harder. Smith said the $500 payment she received went to food, electricity and water bills, and gas for her car.

Smith’s family drives two hours to Great Falls because she said the groceries are cheaper there. Local initiatives like buses that run through the reservation providing three meals for children each weekday and federal programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program have helped.

Smith also deals with housing problems. Her toilet is often plugged up, parts of the ceiling have caved in and gaping holes dot the walls.

While the federal government disbursed funds to tribes to address COVID-19 related issues, members of the Blackfeet Nation still struggle despite the historic levels of aid. (Video produced by Mackenzie Wilkes/News21)

Substandard living conditions and poor infrastructure, compounded by Indigenous communities’ disproportionate rates of heart disease, diabetes and other diseases, can make them vulnerable to COVID-19.

The Blackfeet Nation had high vaccination rates, with more than 8,700 people on the reservation inoculated by Aug. 11, according to the tribe’s COVID-19 Incident Facebook page. There have been 48 deaths from COVID-19 in a community of around 10,000 people.

The tribe is set to receive an estimated $81 million in funding from the American Rescue Plan Act this year, McNeely told the Glacier Reporter. The U.S. Department of Treasury’s Office of Recovery Programs said as of July 20, $13.2 billion of these funds have been disbursed. The second round of payments is expected to begin mid-August.

Tribal member Richard Horn looks out over Badger Creek in the Heart Butte region of the Blackfeet reservation near Browning, Montana. (Beth Wallis/News21)

Richard Horn, an educator and traditional elder, lives in the Heart Butte community — a rural section of the reservation 26 miles south of Browning.

Horn said because of the expansive landscape of Montana’s terrain and poor infrastructure investment in the community, Heart Butte experienced disproportionate effects from COVID-19, and the impact of federal dollars in the Heart Butte community has been minimal.

The reservation’s food insecurity rate is 69%, compared to the national average of 12.5%, according to the Blackfeet Tribal Health Department’s community health assessment from 2017.

Indigenous communities have experienced at least 2.2 times more COVID-19 cases compared to white people in Montana. Indigenous COVID-19 deaths are 1.7 times the number of white deaths, according to recent data from the CDC.

“We’re a communal people and we seek tranquility and solace in each other,” Horn said. “It was really hard because we couldn’t mourn in the way that would be psychologically feasible to mourn because of this COVID. Everyone, I think, suffered more from that than even the actual losing of people.”

Health disparities affect Native Americans in urban settings as well. Roughly 70% of Native Americans reside in urban areas, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, but most Indian Health Services funding is directed to tribal health facilities.

IHS received over $1 billion in CARES Act funds. Of the $600 million immediately distributed in April 2020, $570 million went to IHS and tribal health facilities, while only $30 million went toward the 41 health programs in the Urban Indian Organizations.

Being able to provide specialized care for Indigenous people who live off-reservation is the obligation of the federal government, according to Kerry Lessard, executive director of Native American LifeLines, an IHS-contracted referral service.

“A person’s tribal citizenship doesn’t change just because their address does, and so any trust in treaty responsibilities the federal government has to tribal citizens doesn’t stop just because they leave the reservation,” Lessard said.

According to Wendy Carrión, director of health services at the Sacramento Native Health Center, roughly 46% of their patients have multiple preexisting conditions, making them vulnerable to severe effects from COVID-19.

Carrión said the urban health program found its patients wanted information and care from officials who understood the needs of Indigenous people. It was also important, she said, to provide not only Sacramento’s Indigenous populations with vaccines, but other races and ethnicities as well in order to protect the Native American community.

“We needed to focus on the Native community and make sure that … they have access to both testing and immunization,” Carrión said. “But in order to keep the community safe … we were able to talk to them and be able to expand it to the rest of the community.”

Also impacting the response to the pandemic is data collection and funding, according to Dr. Spero Manson, an epidemiologist and director of the Colorado School of Public Health’s Centers for American Indian & Alaska Native Health.

The state of Maryland, for example, isn’t tracking COVID-19 cases among Native Americans.

“If we are to understand the health status of the Native community and to make sure that interventions and funding are being what they need to be, you have to report on us,” said Lessard. “But more than that, it is figuratively and literally saying you don’t count — we’re not counting you, you don’t count.”

Members of the Ancestral Guard paddle out on traditional redwood canoes in the Klamath River on the Yurok reservation in Klamath, California. (Beth Wallis/News21)

Some tribes have used federal funds to address underlying issues exacerbated by the pandemic. In addition to distributing COVID-19 relief checks to members, installing broadband infrastructure and building an emergency response center, the Yurok Tribe used CARES Act funds to address ongoing food security issues on the reservation.

The Yurok Tribe Reservation, nestled along a stretch of the Klamath River, sits in Northern California. The tribe, which has more than 5,000 members, was declared a food desert by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2017. The pandemic, as well as other crises in the last several years, has made tribal members aware of the ongoing food insecurity in the area.

Forty acres of grassy meadows, daisy-covered hills, towering redwoods and huckleberry brush are becoming “food villages,” which will comprise gardens, a commercial kitchen and tiny homes. This land — the ancestral land of the Yurok people — was purchased with the tribe’s CARES Act allotment for $490,000, according to property tax records.

Walking along this land, Taylor Thompson, manager of the Yurok Tribe’s food sovereignty division, established in August 2020, said having a sustainable food source was important in case of a crisis.

“What can we do to make sure that we are able to sustain ourselves in case of a large-scale catastrophe?” Thompson said. “COVID-19 was kind of an eye-opener that sometimes larger systems go down. So what can we do to make sure that we can help support our people through those tough times?”

The Yurok Tribe received $40,181,881 in total CARES Act money from the Coronavirus Relief Fund. The money, in part, is being put toward food security.

Thompson said the food villages would create sovereignty for the Yurok Tribe by giving members the ability to provide food for themselves.

The pandemic exacerbated different infrastructural issues in Indigenous communities across the country. With the federal government allocating a historic amount of funds to tribes, some of them, like the Yurok Tribe in Northern California, are using the money to create solutions. (Video produced by Mackenzie Wilkes/News21)

Sammy Gensaw, a Yurok member, has been working toward food sovereignty among the North Coast’s Indigenous communities since he was a teenager. Gensaw co-founded the organization Ancestral Guard, which teaches Indigenous youth farming and fishing, as well as provides families a sustainable way to obtain food.

“Sovereignty for me means that we have the ability to maintain and we have the ability to improve the system that we’re part of, that our ancestors laid down before us to give us guidelines on how to provide these healthy opportunities,” Gensaw said. “So when we say sovereignty, we’re not just talking about political terms. We’re not just using buzzer words. When we say sovereignty, we want our people to be able to make healthy decisions.”

As Gensaw paddled along the Klamath River in a hand-carved redwood canoe, he talked about how the North Coast’s Indigenous communities need to adapt to ensure food security and to protect their land and water. The Yurok traditionally fish, but moderate to extreme drought and a parasite spreading in the Klamath River are killing off the Chinook salmon.

Drought and lack of healthy food prompted Gensaw to start the Victorious Garden Initiative and show that fishermen can be farmers. He said while the Yurok are traditionally fishermen, teaching youth to garden will provide a stable source of food.

“We’re not just growing food; we’re not just giving it to people,” Gensaw said. “We’re trying to revitalize the idea that these gardens are a piece of our culture, because often in Indian Country, traditions and cultures get muddled together. And in reality, these traditions are things that our fathers have done, our grandmothers have done and their grandparents have done and we’ll continue to teach our children.”

On the Navajo Nation, there have been more than 31,000 cases of COVID-19 and more than 1,300 deaths. According to the 2020 U.S. Census, there are 172,813 people living on the reservation, the majority being Navajo. At times throughout the pandemic, Navajo Nation has used daily curfews, lockdowns and mask mandates to curb the spread of COVID-19.

The Navajo Nation received $714,189,631 in CARES Act funding from the U.S. government — a 225% increase in funds from what the nation normally receives. As $1.86 billion in first-round American Rescue Plan Act funds rolls into the Navajo government’s coffers, tribal officials are deciding how to distribute this new financial opportunity.

Navajo Nation Police Chief Phillip Francisco at his desk at the Navajo Nation Division of Public Safety and Central Command Headquarters in Window Rock, Arizona. (Beth Wallis/News21)

According to Navajo Nation Police Chief Phillip Francisco, the police department requested $36 million in resources from the CARES Act and received only hazard pay and personal protective equipment. He said he’s hopeful this round of American Rescue Plan Act funding will address long-running infrastructural deficiencies and provide an opportunity for the department’s “renaissance.”

With about 200 commissioned personnel, the department is stretched thin from answering hours-long calls on rural dirt roads — often to homes so remote they don’t have addresses, with radios whose signals don’t cover remote service areas.

To adequately police Navajo Nation, a study commissioned by the police department from Boston-based consultant group Strategy Matters recommended boosting staff to 500 personnel, minimum. Ideally, the report said, staff should be around 775.

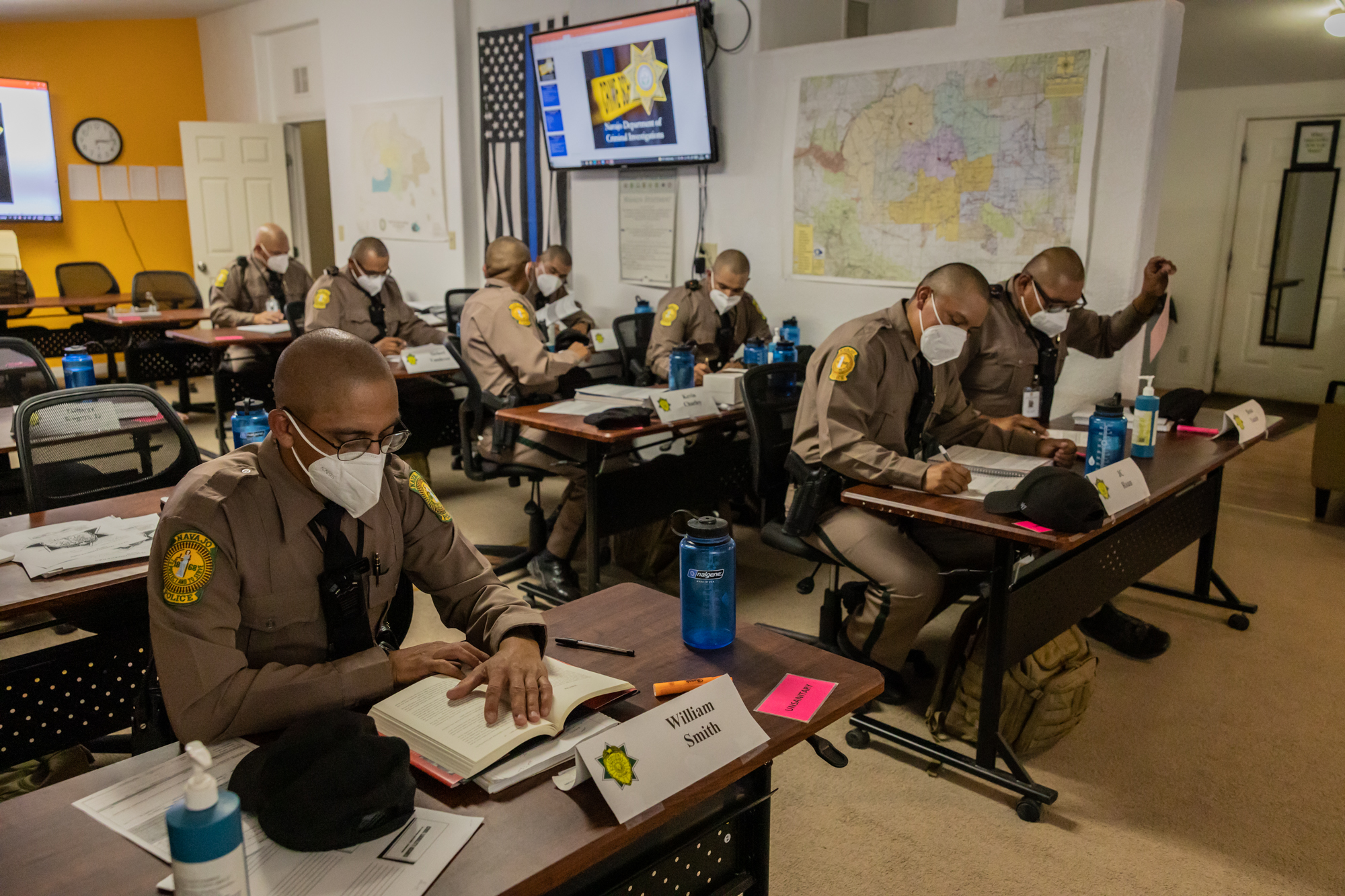

The report said the department must also expand its facilities to house more staff. Francisco hopes American Rescue Plan Act funds will help upgrade, among other facilities, a 71-year-old building with “extremely elevated and significant airborne fungal spore counts,” a converted post office created after a station was condemned and a training academy made from two double-wide trailers.

“That’s really the biggest drawback here on Navajo Nation,” Francisco said. “We don’t have that infrastructure and haven’t had it for a long time.”

During the pandemic, officers have been enforcing curfews, operating educational checkpoints, distributing PPE and transporting arrestees to the hospital for COVID-19 tests before booking. Captain Leonard Redhorse of the Navajo Nation Police Department said officers often worked 16- to 24-hour shifts to cover colleagues who were sick or had to quarantine due to exposure. Officer vacation time was canceled because the department was stretched so thin.

The silver lining of potential American Rescue Plan Act funding for his department, Francisco said, is something good that came out of a “very challenging year.”

Left: Navajo Nation Police recruits run on sand dunes for physical training in Chinle, Arizona, on the Navajo Nation reservation. Right: Navajo Nation Police recruits study inside the training academy in Chinle, Arizona. The academy is housed in two double-wide trailers, which limits recruitment class sizes. (Beth Wallis/News21)

For its citizens, the Navajo Nation government allocated $1,350 for adults and $450 for children to approved applicants. Navajo Nation Council Delegate Eugenia Charles-Newton said funds were used for a variety of needs, including installing bathroom additions, water cisterns, broadband/cell phone towers and septic systems, and bringing electricity to more than 1,000 homes through on- and off-grid methods.

One citizen, she said, bought a generator to power his house — the first time he was able to turn on electricity in his home. A homeless single mother with three children used their checks to purchase an old travel trailer to live in. Charles-Newton said families were able — often for the first time — to purchase new beds and bicycles for their children.

“It was wonderful to just see that our Navajo people all had different needs, but they were all addressing it in different ways,” Charles-Newton said.

Roy Slowman, who grew up herding sheep on the reservation, said he used his federal stimulus money to move from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to the Red Mesa region of the Navajo Nation for a job transfer. Slowman, a utility system operator for IHS, moved into a hogan — a roundhouse commonly found on the Navajo Nation — with no running water and a dirt floor used for traditional purposes.

At the beginning of 2021, his cousin — whom he considered a brother and who lived in a house on Slowman’s family land — died, so Slowman moved from the hogan into the house, which had running water.

Using his tribal assistance check, Slowman traveled to the Midwest to pick up a reliable vehicle from his adult children that he could use to get to and from work.

“I’ve been away 26 years. And right from day one, I wanted to be here,” said Slowman, sitting in front of his new house on the land on which he grew up. “I have always called this home.”

Roy Slowman, a Navajo Nation citizen, outside of his house in Red Mesa, Arizona, on the Navajo Nation reservation. (Beth Wallis/News21)

The CARES Act and American Rescue Plan Act brought unprecedented levels of funding to Indigenous communities across the U.S. These funds allowed some tribes to address ongoing infrastructure issues exacerbated by COVID-19, including food security, water access and emergency response.

Sen. Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii, Senate Indian Affairs Committee chair, said more investment from the federal government is needed for long-term improvements of infrastructure in Indigenous communities.

“It is a shame that it took a global pandemic for us to recognize how these unmet needs put Native communities behind the eight-ball when it comes to health care and economic recovery,” Schatz said at a roundtable meeting in June. “As Congress acted to address both, it became clear that federal investment in building new and updating existing infrastructure in Native communities was no longer ‘nice to have’ but actually essential.”

For Richard Horn of the Blackfeet Nation, efforts toward bolstering essential infrastructure continue while his tribe is recovering from the long-term implications of COVID-19. The trauma members of his tribe experienced from the pandemic, he said, will leave a lasting impression.

“It was a whole new learning curve and very traumatic,” Horn said. “We had to relearn and rethink all of the things that made us close. We had to step away from it. And among the people in my community, the effects still linger.”