Illustration BY SARA METZ

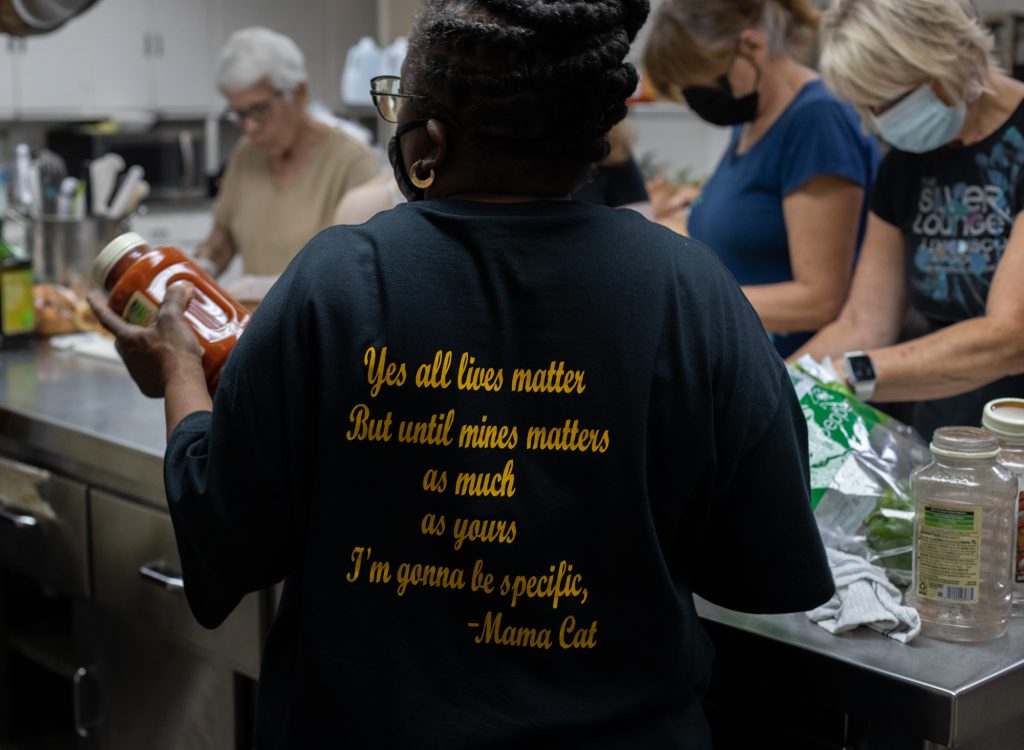

At noon every Thursday, Cathy “MamaCat” Daniels begins her mission to feed St. Louis, Missouri’s homeless population — the people she calls her “unhoused family.”

In the basement of a church in an affluent St. Louis neighborhood, Daniels and other volunteers get ready to cook mass quantities of spaghetti and meatballs, or whatever meal she’s decided to cook for the night.

“When I come in here I’m going to cook food that’s going to nourish the body,” Daniels, once unhoused herself, said. “We feed the body, we feed the spirit.”

In a few hours, she’ll have meals to distribute later that night to people who live on St. Louis’s streets. Although she stands at 4 feet, 9 1/2 inches, she rules over her kitchen kingdom and makes it look as if feeding over 100 people is easy — because, for her, it’s just another day in the life.

Daniels has cooked meals once a week since she founded PotBangerz in 2014 — an organization which feeds and houses the homeless community. But COVID-19 changed her routine — at first because fewer homeless people were on the streets, but later because an increased number of people found themselves in need.

Daniels said St. Louis city officials made hotels and shelters more available to those who are homeless when the pandemic began but later, the crisis of COVID-19 exacerbated struggles.

Soon, as people feared eviction and had little money, Daniels said, she began seeing a larger number of people experiencing homelessness.

“People were afraid,” Daniels said. “A lot more people were put in that transient mode.”

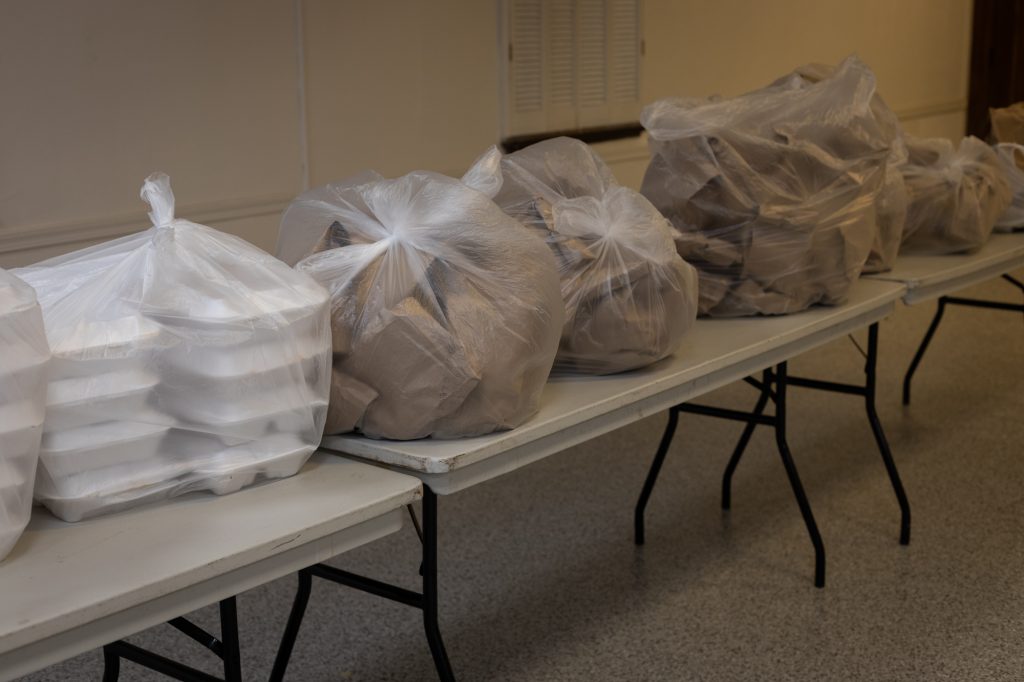

At times during the pandemic, Daniels said, she had to step up her operations to feed more people.

“We’ve done as many as 210 meals,” Daniels said. “The need did increase.”

Even with that increase, PotBangerz never

stopped cooking.

“We didn’t miss not one Thursday,” Daniels

said.

Daniels said as PotBangerz cooked meals, the organization also focused on helping families find permanent housing.

The latter part of that task, Daniels said, became more difficult during the pandemic. Shelters could not take as many people as usual because of social distancing constraints. People found themselves homeless for the first time, and they did not know what to do or where to go.

Janet Burns, known as “Fifth Degree,” said she received help from Daniels during the pandemic. As a single mother of three, Burns was homeless during COVID-19. She said Daniels helped her family into shelters and made sure they had food.

“She picked us up, and she got all our things. And she took us to the Salvation Army — that was the first (shelter) — and she had let us know, ‘They’ll be able to help you. If you need me for anything, you give me a call,’” Burns said. “She has invested a lot of love and time into me and my kids.”

From Daniels’s perspective, federal relief benefits did not help the families she served enough.

“You can’t just throw money at people and say, ‘Here, go for it,’ especially if they don’t know what to do with it,” Daniels said.

Daniels said despite pocketing some money from the government, families still faced the risk of eviction. Some families did not know how to fill out paperwork to ensure they did not get evicted, she said.

To help mitigate that issue, Daniels said, she and PotBangerz went door to door helping at-risk St. Louis residents fill out documentation so landlords could not evict them.

Still, in St. Louis and in households nationwide, families struggled to make ends meet, putting them more at risk for homelessness and food insecurity.

Even families who were not transient experienced issues with hunger throughout the pandemic. During the pandemic, one in six households reported food insecurity in the United States.

Experts said when people do not have enough money to pay for basic needs, food often comes as a last priority.

“Often what we see is that when families have to make decisions about what to cut in their budget if they don’t have enough cash resources, that food is often the first thing that gets cut,” said Allison Bovell-Ammon, policy director at Children’s Health Watch.

In response to heightened food security troubles, Daniels saw organizations rise to meet the needs of a hungry community.

“People came out of their silos and started doing these food drives, food giveaways,” Daniels said.

Even households that could afford food struggled to find healthy options in majority Black zip codes of St. Louis, Daniels said.

“Why do we have to eat the trash? We did that during slavery — why are we still doing it? That’s a problem,” Daniels said.

And in St. Louis, segregation has led to systemic inequities.

Certain zip codes are plagued by poverty, making residents more vulnerable to adverse health outcomes, food insecurity and eviction during the pandemic, among other issues.

St. Louis’s residents call the area “the Delmar Divide.” To the immediate north of Delmar Boulevard, houses with rusted fences, missing roofs and broken windows line the streets. To the immediate south, mansions and high-end grocery stores fill the neighborhoods.

“South, you have all the mansions, affluent,” Daniels said. “And then, when you get north of Delmar, all these buildings are dilapidated. You’ve got people where they’re flooded with drugs, alcohol, liquor stores. … It’s all put there for a purpose. We’re talking about intentional dilapidation.”

In a neighborhood immediately north of Delmar Boulevard, zip code 63106, nearly one in every two residents lives below the poverty line. Nearly 90% of the residents in the zip code are Black.

In a bordering neighborhood, zip code 63102, mostly south of Delmar Boulevard, fewer than one in ten residents live below the poverty line. Nearly 50% of the residents in the zip code are white.

And during COVID-19, vulnerability to disease in neighborhoods north of the divide left communities of color disproportionately affected.

A study published by the Center for Urban and Racial Equity found Black residents of St. Louis experienced COVID-19 very differently than white residents. While about 47% of St. Louis residents are Black, nearly all of the city’s residents who died from COVID-19 were Black.

The trend goes beyond St. Louis, Aaron Brink-Johnson, co-author of the study, said.

“I would say that there definitely are Delmar Divides everywhere. I don’t know that they’re always as noticeable,” Brink-Johnson said. “But I do think that those sorts of inequities … are present in cities across the country.”

And for those communities, the disproportionate effects of COVID-19 will linger, Brink-Johnson said.

“When there’s inequities in how Black communities, communities north of the Delmar Divide are experiencing COVID, that’s going to also have disproportional effects on other aspects of life as well,” said Aaron Brink-Johnson.

Even as communities north of the divide experience this, they also struggle with displacement and eminent domain. Black communities north of the Delmar Divide have been displaced, and according to Daniels, some displaced residents have moved up to north St. Louis County, where she lives.

“Segregation was legal here in St. Louis, and the remnants of it are still evident, especially north of Delmar,” Daniels said.

Daniels said the increased crime in her neighborhood has caused her to feel less safe in her own home.

For that reason and others, she said, she will be leaving St. Louis.

Daniels plans to move with her husband, her grandchildren and other family members to Jacksonville, Florida.

But her impact on St. Louis will be lasting.

“We fed thousands of people from around the world that were on the streets protesting … and our unhoused family. Also, the families we help with shelter, groceries and basic needs” Daniels said. “I honestly have no idea of the numbers. Way too much to count.”

Daniels said her weekly meals will continue under the direction of her fellow Pot Banger, Ariel Rangel.

In September, Daniels said, she will be back in St. Louis to cut the ribbon on the transitional house for women that she and PotBangerz created. The house will give six women at a time comfortable shelter, a community garden in the backyard and a kitchen.

“I’ve got a kitchen, baby,” Daniels said. “Those that don’t know how to cook, we’re going to teach them. Each one, reach one, so we can teach one. That’s my thing.”

Daniels said that in cities with stark socio-economic divides, it’s critical to come together.

Daniels will create another, albeit different, iteration of PotBangerz in Florida with her daughter.

“The people united will never be defeated,” Daniels said.