Illustration by Zach Van Arsdale

The sound of the phone ringing woke Peter Young, 27, from his nap.

He was sleeping in a hospital bed in Los Angeles as part of a five-day clinical trial that demanded he have his blood drawn every two hours. It’s not a job most people sign up for eagerly, but for Young, it seemed like a dream opportunity. Young delivers food for Postmates full time.

“This will pay a lot more for the time I am spending than rideshare,” Young said. “I’m in a hospital bed right now. That’s why I was napping — because I am physically beat up.”

Young has been a part of the “gig economy,” working for rideshare and food delivery apps, for about four years. He used to drive for Uber and Lyft, but since the pandemic, he’s been doing strictly food delivery. While Young relies on the income from Postmates to survive, he said the job’s unreliability is taking a toll on his financial and mental well-being.

“I can’t plan for the future,” Young said. “I can’t be confident in what income I will have in six months and that is really stressful.”

In a gig economy, workers don’t have a contract with an employer or benefits, but are freelance delivery workers or drivers called to service through apps such as Lyft or DoorDash. Such work can give people flexibility and freedom but some experts believe it also exposes them to inconsistent, low pay and the possibility of exploitation for the sake of customer convenience. The work became even riskier during COVID-19, which put thousands of people out of jobs. Gig workers are planning a strike for mid-July.

“While they don’t have long-term security from a particular organization and also a lot of the benefits the organizations provide people with, they exchange that for being able to have greater control over what kind of work they do when they do it and how they do it,” said Dr. Brianna Caza, associate professor in the Department of Management at University of North Carolina Greensboro.

A transition to food delivery in COVID-19

In the wake of the pandemic, many drivers for rideshare were unable to find work driving for Uber or Lyft because of the risks associated with the pandemic.

Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi reported on a call with investors in May 2020 that COVID-19 decreased business by 80% in April 2020. However, Khosrowshahi said 40% of active rideshare drivers switched to the Uber Eats platform in April 2020.

Jesenia Rodriguez, of New Haven, drove for Uber and Lyft, but stopped in March. She tried switching to DoorDash.

“Due to the way they were paying I was risking myself for two or three dollars,” Rodriguez said.

She tried to apply for unemployment, but because she was still considered an employee of Uber and Lyft, her application was declined.

“They knew I was an employee through Uber so when I applied due to the pandemic due to the situation, no one responded with anything,” Rodriguez said. “I haven’t gotten any unemployment at all.”

Rodriguez’s rent is subsidized through Section 8 housing and she receives food stamps to feed herself and her son, but life has not been easy. She has determined that not working at all is a better option financially than returning to DoorDash.

“I had to pick up in Walmart, three different orders for only $3 each,” Rodriguez said. “I have to put gas in the car and if anything breaks down I have to pay for it. Right now I am not in that position.”

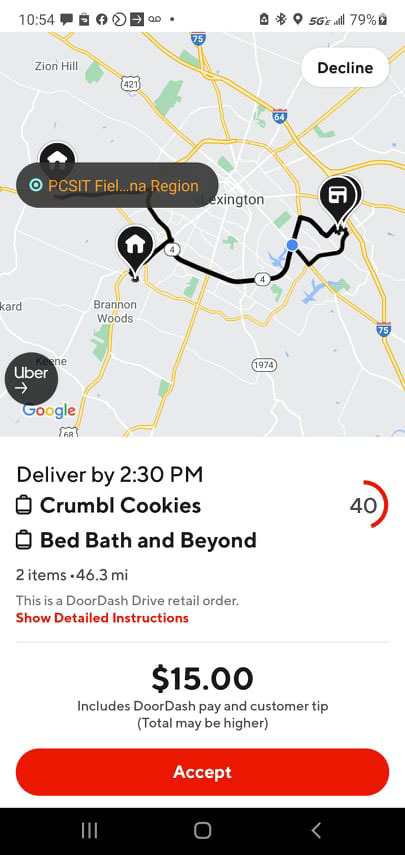

During the pandemic, Chance McNamara of Lexington, Kentucky, worked at DoorDash full time, which he said did not provide him with a survivable income.

“You don’t really make enough to make a living out of it,” McNamara said. “You don’t really make enough to pay your rent to almost not even pay your utilities, because it’s going towards food, that’s going towards gas, that’s going toward car repairs.”

A spokesperson for DoorDash said 2 million delivery drivers joined the platform from March through September 2020.

Some college students or recent college graduates worked at DoorDash during the pandemic to make spare cash. Wills Rice, a recent college graduate from Scottsdale, Arizona, said while he enjoys the income from DoorDash, it is not his only job and he has no dependents.

“There’s some days where I could make $130 in five hours, but there’s also times where I could make $60 in five hours, which is a lot slower on a certain day,” Rice said. “And I think if you’re someone that’s relying on that to pay your bills, to feed your family, to do all that, I don’t think it’s reliable enough because it’s based on when people are ordering food. It’s not necessarily a job where you have a certain amount of time and amount of hours every week.”

McNamara points to one delivery more than 45 miles away where he netted $15, with no tip.

A spokesperson for DoorDash reported that 85% of Dashers are students or have a full or part-time job. Dr. Katie Wells, PhD, an Urban Studies Foundation postdoctoral research fellow at the Georgetown University Global Cities Initiative, said there is no independent data on the industry.

“This is a story that these companies like to tell, because that’s an easier sell as opposed to one to say that actually there’s no data showing this vast majority of rides are produced by part timers,” Wells said. “In fact, it’s the opposite. The majority of drivers are like those in our study that are full-time. They’re working really hard to support their families and can’t make a go of it.”

Who has ‘control’ in the gig economy?

Some workers in the rideshare and food delivery industry, say the app companies have all the power.

“I don’t feel like I have control over anything,” Young said. “They control the flow of my day through an app. They can pay different amounts at different times a day. They can get me to work when they want me to work. And rather than having more control of my job, I feel like I have no control over my job.”

Young said when he started driving for Uber and Lyft four years ago the wages he earned were sustainable. He made about $130 in an eight-hour workday minus the price of gas, which was about $20 per day. That averages out at about $13.75 an hour.

However, as time went on, the wages he earned from Uber slowly began to decline. A union spokesperson said the pay trend is industry wide.

“They change the way they compensate us, and it was done under duress, so in order for us to continue working even with arbitrations and things like that, every time they decide they want to change the contract, you have to agree to it,” said Beth Griffith, board chair and executive director of the Boston Independent Drivers Guild and a driver for Uber and Lyft.

Griffith said she was making a decent amount of money driving for Uber and Lyft until the way the drivers were paid was updated and she was forced to agree to the new terms. Uber got rid of a payment model known as the “numeric multiplier” and Lyft got rid of its model, known as “prime time” in 2016.

Under the apps’ previous models, Griffith would drive the night shift. She said she would be compensated about 1.5 or two times the fare for driving during the night. Under the new plan, drivers were paid per mile and per minute.

Uber dropped its pay rates per mile from $2.15 to $1.75 in 2017 and in 2019 from 80 cents to 60 cents, according to accounts from riders. Uber and Lyft do not publicly report data. Griffith and Young were unsure of the exact amounts but their estimates lined up with the amounts reported by other drivers.

Uber, which recently acquired Postmates, and Lyft did not respond to requests for comment. In April 2021, Uber released median earnings for drivers in six U.S. cities. In Los Angeles, Uber reported a median hourly wage of $26.85.

Wells said the math is not always that simple. She studies Uber drivers in the Washington D.C. area. She has been following 40 drivers who drove for Uber and moved in and out of the industry over time, including during the pandemic.

“The vast majority of these jobs are extremely low paid and exploitative, but it’s really, really hard to figure that out because the costs are so nebulous – like a spreadsheet of 20-some different factors to figure out, what do they get paid?” Wells said. “One of our drivers sort of said very early on, ‘My God, this makes McDonald’s look like a simple job because at least you’re not going to lose anything at the end of your shift.’”

Gig workers demand rights

Rideshare and food delivery drivers in some of America’s largest cities, including San Francisco and Boston, plan to strike July 21 to raise awareness about the impact of the gig economy on workers.

“We know that the only way to guarantee that these companies pay a good living is if we have a legally binding contract that we collectively bargain with these companies,” said Nicole Moore, an organizer for Rideshare Drivers United.

“The situation they have us in is not one that is sustainable for our own lives or for the communities we live in,” Moore said.

Moore has been driving for Lyft for four years in Los Angeles to help support her family on top of another job. She stopped driving when the pandemic began because of safety concerns and a lack of demand for Lyft rides, especially at the beginning of the pandemic.

She got involved with efforts to unionize rideshare drivers after getting fed up with the declining pay.

“There’s very little trust between drivers and the apps anymore,” Moore said. “They always spin things to make us think that we’re about to get something great when it’s something when they cut the mileage rate.”

Moore and other drivers began to see a pattern where the drivers were getting a smaller and smaller cut of the price of a ride, but realized they had no platform to negotiate or demand rates. And, she said, some full-time drivers became frustrated after receiving no health benefits or paid time off.

“The companies are really trying all over the country to deceive the public and drivers about their sweetheart deals, like a guarantee of flexibility, which is not a guarantee at all,” Moore said. “Drivers in California will tell you that we’re not making more and we’re making less.”

Drivers in Connecticut are also fed up, according to Rodriguez. She is an organizer with Connecticut Driver’s United who hopes her efforts will make life easier for workers like her.

“We literally need help,” Rodriguez said. “I am lucky because I have Section 8. Imagine the people who don’t have Section 8. This is the reason why Uber and Lyft need to come up with something better for us because they only think about making their money and their customers. They don’t think about us.”

Griffith, in Boston, is trying to organize the workers in her organization to strike and hopes the movement will spread to other cities. The strike will come in the midst of a shortage of Uber and Lyft drivers across the country. Moore said there is no surprise drivers were not eager to rush back after the pandemic.

“It’s not what America wants,” Moore said. “America wants good jobs. They want to know that when they get a car, that person has had enough sleep because they’re earning enough money that if they work eight hours a day, they can make a living.”